Spectacular

The robbery of the century

In 1986, the immensely valuable treasure of Loreto was stolen from the City Museum of Klausen: The chronicle of the most sensational art theft of that time in Italy and the return of the treasure to Klausen in stages.

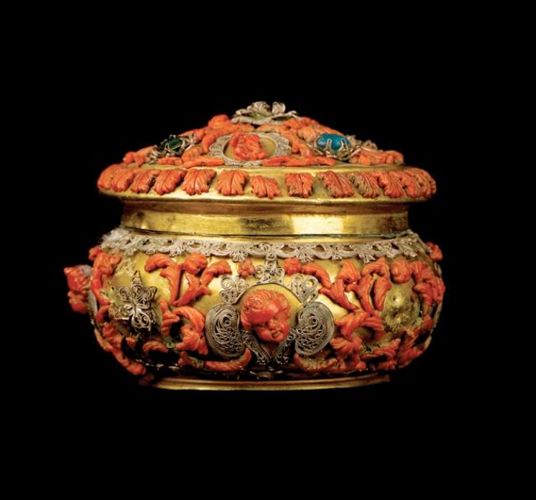

A spring Wednesday night in Klausen, sometime between 2 and 4 a.m., May 27, 1986 is thus only a few hours old. The people of Klausen are in deep sleep. In Frags, the southern district of Klausen where the Capuchin Church and the City Museum are located, the lights go out. The power failure is not noticed by anyone. But when museum keeper Josef Haniger enters the City museum at half past nine in the morning, he imagines himself in a nightmare: the majority of the unique treasure of Loreto is no longer in the display cases. More than 50 works of art such as paintings from the Rubens School, gold and silver chalices, Chinese porcelain from the Ming Dynasty - stolen.

"The perpetrators knew their way around, they even knew about circumstances that were certainly familiar to only two or three people," says Heinrich Gasser, mayor of Klausen at the time. For example, the thieves knew how to cut off the power supply in the district around the museum. They knew about the invisible steel door in the museum, hidden behind a wall. They punched a hole in the wall and welded a circular opening in the door behind it. Just big enough to get into the museum's showroom. "They had deactivated the alarm system with a nail beforehand," says Heinrich Gasser, "The burglars were very careful, they didn't smash any display cases, and a painting that didn't fit through the opening they simply left next to it." A multitude of inconsistencies. A lot of inside knowledge that the thieves have. Speculation is flourishing. The most spectacular art heist of that period in Italy must have been carried out by specialists, commissioned by - who? Perhaps the drug mafia?

A spring Wednesday night in Klausen, sometime between 2 and 4 a.m., May 27, 1986 is thus only a few hours old. The people of Klausen are in deep sleep. In Frags, the southern district of Klausen where the Capuchin Church and the City Museum are located, the lights go out. The power failure is not noticed by anyone. But when museum keeper Josef Haniger enters the City museum at half past nine in the morning, he imagines himself in a nightmare: the majority of the unique treasure of Loreto is no longer in the display cases. More than 50 works of art such as paintings from the Rubens School, gold and silver chalices, Chinese porcelain from the Ming Dynasty - stolen.

"The perpetrators knew their way around, they even knew about circumstances that were certainly familiar to only two or three people," says Heinrich Gasser, mayor of Klausen at the time. For example, the thieves knew how to cut off the power supply in the district around the museum. They knew about the invisible steel door in the museum, hidden behind a wall. They punched a hole in the wall and welded a circular opening in the door behind it. Just big enough to get into the museum's showroom. "They had deactivated the alarm system with a nail beforehand," says Heinrich Gasser, "The burglars were very careful, they didn't smash any display cases, and a painting that didn't fit through the opening they simply left next to it." A multitude of inconsistencies. A lot of inside knowledge that the thieves have. Speculation is flourishing. The most spectacular art heist of that period in Italy must have been carried out by specialists, commissioned by - who? Perhaps the drug mafia?

_Thomas_Rötting.jpg)